First, some background on the history of gaming companies in Malaysia,using Berjaya Sports Toto as an example:

Sports Toto Malaysia Sdn Bhd was incorporated in 1969 by the Government of Malaysia. The eighties witnessed the making of a significant milestone in Sports Toto’s corporate history. The Company was privatised on 1st August 1985, relinquishing henceforth, status quo as a state-owned gaming enterprise. Sports Toto is currently a wholly-owned subsidiary of Berjaya Sports Toto Berhad which is listed on the Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange.

(http://sportstoto.com.my/m_info/profile.htm)

Another more complete version of Sports Toto's history was provided by the Business Times,27 May 1987.

Sports Toto, which will become the second gambling enterprise in Malaysia to be listed (after Magnum Corp), was privatised in 1985, with the government retaining a 30% stake. Presently, bumiputra-owned B and B Sdn Bhd owns 60% and the Melewar group 10% of the company's M$1m capital, which is to be expanded to M$30m before the public offer. This is likely to consist of 5.25m shares of M$1 each, or 17.5% of its enlarged capital, priced at M$2 a share, with B and B offering 4.5m shares, reducing its stake to 45% and Melewar 0.5m shares, diluting its stake to 7.5%.

Then later, in 1988,according to the Financial Times UK, on 12 May 1988:

B and B, owned by Mr Vincent Tan and Malay businessmen believed to be nominees of prominent politicians, will buy 20.1 per cent of the Raleigh group for 38.8m ringgit (US$15m). Raleigh itself has announced two acquisitions: a 32.8 per cent stake in Sports Toto, a fast-growing lottery organisation, and a 55.3 per cent stake in the diversified Berjaya Corporation. Raleigh is paying nearly 90m ringgit for its Sports Toto stake, acquired mainly from the Ministry of Finance, and some 190m ringgit for the holding in Berjaya which is controlled by B and B. Berjaya holds 52 per cent of Sports Toto, 48 per cent of Regnis Malaysia (distributor of Singer products), 28 per cent in South Pacific Textiles, and 19 per cent in United Prime Insurance.

Readers ought to note that as at March 22 2006, B and B was registered only as

a business name, not as a company.

And now to the judgement where it was held that gaming licenses cannot be transferred or assigned.

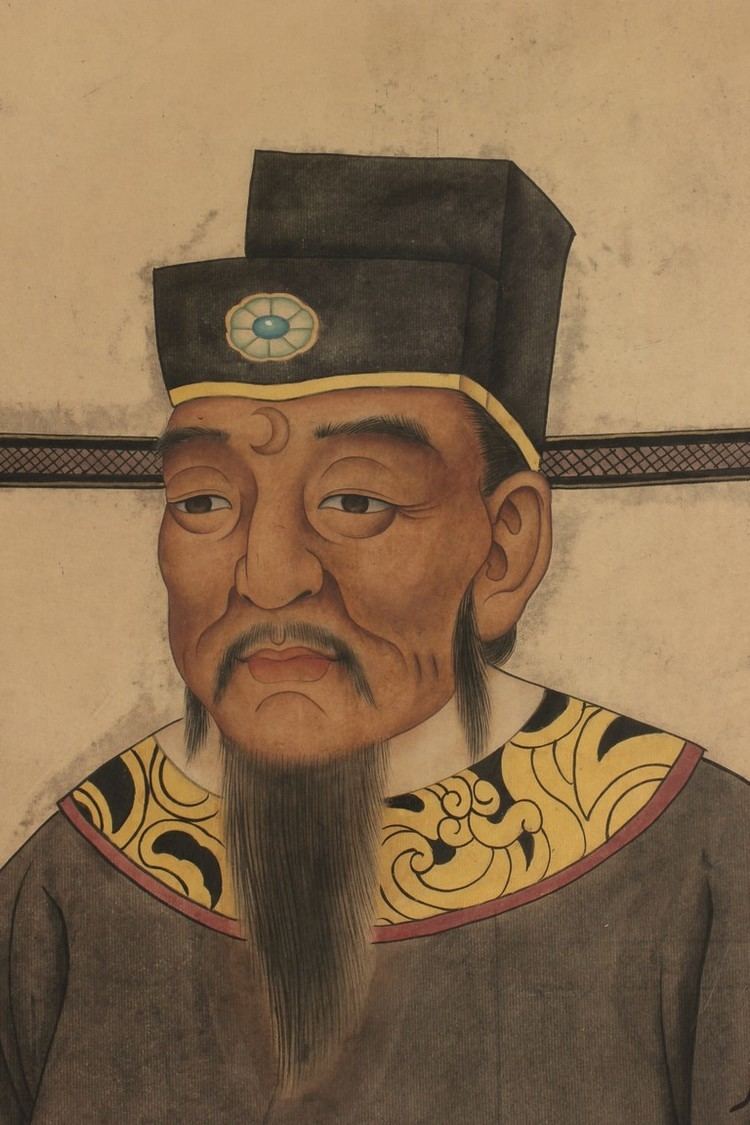

DATUK YAP PAK LEONG V SABABUMI (SANDAKAN) SDN BHD

[1997] 1 MLJ 587

GOPAL SRI RAM, ABDUL MALEK AHMAD AND MOKHTAR SIDIN JJCA

Judgement written by very learned Sri Ram:

In regards to Sections 5 and 21 of the Pool Betting Act 1967,and providing their reasons why licenses issued pursuant to the Act cannot be assigned or trnsferred:

In our judgment, these two sections -- ss 5 and 21 -- should be read in this

way. The Minister is empowered to issue a licence to any person to carry out

the activities to which the Act applies. He may impose conditions in the

licence. A person to whom such a licence has been issued may carry on those

activities; whether by himself or by his duly authorized employees or

agents. It is in the public interest that such agents are not undesirable

persons; for example, persons with criminal records. That is why the

Minister in the present case imposed a condition in the new licence

requiring the club to submit for the Minister's approval the list of agents

whom the club wanted to engage.

If any person engages in those activities specified in s 21(1) without a

licence, he commits an offence. If a licensee conducts those activities in

breach of the conditions appearing in the licence, he too commits an

offence. The object is to ensure that only a limited class -- the licensee

and his employees and agents -- conducts gaming business.

When viewed in this way, it becomes clear that Parliament intended not

merely to prescribe a penalty but to prohibit the performance of those

activities set out in paras (a)-(c) of s 21(1). The prohibition is not

express. But it is plain enough for us to discern by necessary implication.If we read s 21(1) in any other way, we will negate its true effect and

frustrate Parliament's true intention.

In interpreting s 21 in the way which we have done, we have had regard to

the whole Act, including its object and purpose. It is plain from a reading

of the Act as a whole that Parliament's intention in passing it was to

regulate and control gaming activity throughout the country. Courts are the

obedient of the will of Parliament as expressed in the words of the written

law enacted by the latter. They must therefore render an interpretation of

the provisions of a statute as best advances the intention of Parliament. By

that we do not, of course, mean that we should re-write a statute. We have

no authority to do so. We must pay heed to the language of the Act and give

it the meaning that advances legislative purpose. And this is what we have

done.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment